“It’s been a day,” were very nearly the first words out of Justin Cronin’s mouth Tuesday evening*, as he took to the podium at the Columbus Circle Borders for a reading, discussion, and signing of his newly released sci-fi/horror epic, The Passage. That day began with an appearance on Good Morning America (“I was on TV” he said, grinning), which was interrupted by no less a luminary than Stephen King, who called in to impart his blessing: “Your book is terrific, and I hope it sells about a million copies. You put the scare back in vampires, buddy!”

*They followed a gracious “thank you” to the Borders employee who introduced Cronin with a summation of all the fuss about the book, and who concluded with the sentiment that despite his excitement for the event, he kind of just wanted to go home and finish reading instead.

Cronin responded to that heady praise with appropriately modulated but obviously sincere gratitude, and this was the affect he carried into the evening’s reading: self-possession and confidence in his own work, combined with full awareness of the good fortune and the efforts of others that have made The Passage the potential “big book of the summer,” as Mark Graham put it in an anticipatory review for this very website.

Before Cronin started reading, he sketched the circumstances of the novel’s conception: four years ago, his then nine-year-old daughter, “concerned that his other books might be boring,” suggested he should write about a girl who saves the world (later in the reading, he elaborated that much of the story was developed in an ongoing game of “let’s plan a novel,” played while Cronin jogged and his daughter rode her bike beside him).

He chose to read from a “transformative” section in Chapter 8, as FBI agent Brad Wolgast’s bond with the orphaned girl Amy deepens, rather than from Chapter 1, saying that the first chapters of novels this size often had to do a lot of “heavy lifting.” The excerpt seemed to go over quite well, with characters ably developed even through such brief acquaintance, a definite sense of the “national exhaustion” in the nigh-apocalyptic U.S., and even a few well-received humorous moments punctuating the darkness.

Afterward, he took questions from the audience, and proved remarkably able to impart interesting information no matter the prompt given—an important skill for a touring author! Asked how long the book took to write, he at first responded glibly “47 years,” before amending to three years of actual writing—but then went on to attest that he really did need his whole life experience, and all the books he had read over those decades, in order to pull this one off. He singled out Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, which he read at age 11 or 12: “It was the first grown up book I read with a surprise ending I actually got. I was reading it at my grandmother’s house in Cape Cod, and when I reached it I was so surprised I knocked a bottle of Mercurochrome off the table. I hope that stain is still there on the carpet. That was an important moment for me.”

The next question was whether the books were a trilogy—and I must admit, this is the sort of question that makes me wish I could send people links like this with my mind—but Cronin managed an answer other than “Yep.” He clarified that “there are three books, but I don’t like the word ‘trilogy.’ That suggests that you can finish this book, but you haven’t completed anything. With each of these, you do come to an end, but they can be taken together as a whole. It’s more of a triptych.”

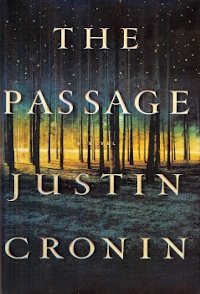

Asked whether he had input into the cover, he talked a bit about all the time, effort, and back-and-forth between various people that had to happen to get the cover right, searching for images relevant to and representative of the book, and revealing that, in the end, he had one major insistence: “I really want stars.” (He got ’em!)

Asked whether he had input into the cover, he talked a bit about all the time, effort, and back-and-forth between various people that had to happen to get the cover right, searching for images relevant to and representative of the book, and revealing that, in the end, he had one major insistence: “I really want stars.” (He got ’em!)

In response to a few other common-to-author-reading questions, he admitted that he took inspiration for his characters from every person he’d ever known (“If you’ve had nearly any interaction with me, I’ll find a place for something about you in a book eventually. That’s just how it is.”), and that he manages to balance writing with the rest of his life because there’s really no alternative—it requires patience, and staying up late, as he writes when his children are either asleep or out of the house.

He took a bit longer responding to a question (full disclosure, my question) regarding whether there were themes he found himself returning to in his work, and what connections he saw between The Passage and his previous novels:

“There’s a difference of scale in the books. The Passage has a bigger plot engine. My prime directive was ‘extreme urgency at every moment,’ and the question I asked of every character was ‘if you are running for your life, what’s the one thing you’ll carry?’ Their answers dictated who they were in the book. But I’ll always write about characters facing hard choices, and the eternal verities: love, honor, duty, courage. And about parents and children. In The Passage, the vampires as a plot engine—yes, I think about this stuff mechanically, sorry if that ruins the magic—but the vampires make us confront the question ‘is it desirable to be immortal?’ And I realized, I sort of already am immortal, because I have kids. The world I won’t get to see is the world they’ll grow up in.”

Next, asked about the movie (the rights were sold in a seven-figure deal to Ridley Scott’s production company), he said that John Logan, who wrote Gladiator, was writing the script, and that he hasn’t seen it yet. They’ll show it to him when they’re done with it, an arrangement that suits him just fine. However, the screenwriter did need to know what would happen in later installments to properly structure the first, and so Logan “now knows more about the next two books than anyone else in the world but [Cronin’s] wife.” Cronin says he’s pretty confident the man can keep a secret, though.

And finally, the questions concluded with an audience member asking about adventure stories that Cronin particularly loved or that had particularly inspired him, and Cronin was happy to offer a list of remembered favorites: kids’ adventures like Swallows and Amazons and Watership Down, post-apocalyptic science fiction like Alas, Babylon and Earth Abides, and almost all the Heinlein juveniles, including The Rolling Stones and Tunnel in the Sky.

After the questions, Cronin sat, signed, and posed for pictures, as is standard practice though I suspect the fact that I saw at least a half-dozen people toting five or six hardcovers each, to be signed without personalization, was less standard; presumably, the hope was that, given the massive hype and overwhelmingly positive reviews, these will either one day be collector’s items, or be eBay-able for profit in the present.

Speaking of those reviews, Cronin did mention he recently received one that mattered more than most: “My daughter just turned 13, and while we’ve obviously been talking about it for years, she just now finally read the book. I was as nervous as I’d ever been giving it to a reader.”

Her verdict?

“She said she liked it, and I believe her.”

Joshua Starr doesn’t want to achieve immortality through his work. He wants to achieve it through not dying.